The Beginnings of the Schengen Agreement

The first countries to move the concept from the debate stage and make it a more concrete reality were France and Germany. These two pioneering countries put an end to the endless debates to set aside differences and look at the positive next steps of integration. This historic event occurred on 17 June 1984, at Fontainebleau, where the two countries framed this shift within the European Council framework. There they set about laying the foundations for the conditions that would allow for the free movement of European citizens and define the conditions that would be required for this to work.

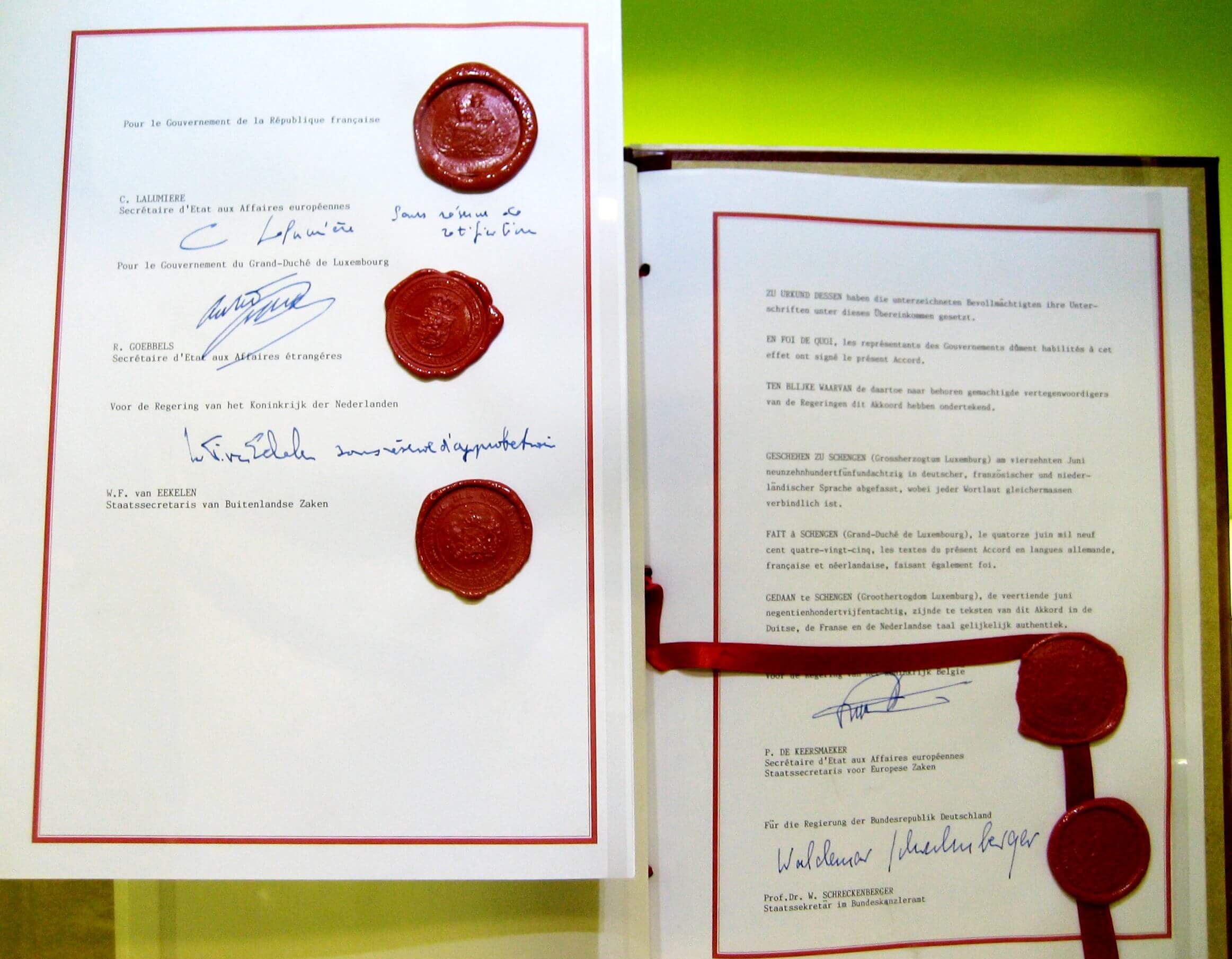

After the initial groundwork that was laid at Fontainebleau, the final outcome of this political movement became what is known as ‘The Schengen Agreement’. This agreement covered the abolishment of internal borders between the signing countries and a strengthening of control over their external borders. This agreement was signed on 14 June 1985, initially by five countries of Europe, in Schengen, which is a small village on the river Moselle in Southern Luxembourg. These signing countries were France, Germany, Belgium, Luxembourg and the Netherlands.

Implementation of the Schengen Agreement

Further concrete steps were taken five years later on 19 June 1990, when a Convention was signed that covered the implementation of the Schengen Agreement. This Convention was concerned with issues such as defining the procedures for issuing a common visa, the abolition of internal border controls, the establishment of a single database for all of the members called the Schengen Information System (SIS), and also setting up a structure for immigration officers where they could coordinate their efforts effectively.

The Schengen Area concept quickly proved its worth and attractiveness to other European countries as evidenced by its quick expansion. Italy joined on 27 November 1990, Portugal and Spain on 25 June 1991, and Greece on 6 November 1992. However, the Schengen Area and Agreement were not fully implemented (including the establishment of treaties and rules) until 26 March 1995 when seven member countries fully abolished their internal borders with one another. These seven countries were France, Germany, Luxembourg, Belgium, Netherlands, Spain and Portugal.

After this event, the Schengen Area expanded quickly and by the end of 1996 6 new countries had joined. These were Austria on 28 April 1995, and Finland, Denmark, Norway, Iceland and Sweden on 19 December 1996. Inspired by this widespread adoption of the agreement by so many European countries, first Italy in October 1997, and Austria in December 1997 also decided to abolish their internal border controls.

May 1999 saw a further significant step towards greater integration of Europe with the Treaty of Amsterdam which was inspired by the progress forged by the Schengen Agreement. This treaty established the agreement within the legal framework of the European Union. Up until that point the rules and treaties that had been set up by the Schengen Agreement had worked autonomously outside the European Union and were not a part of it.

The Schengen Area continued to be enlarged in the next millennium as more countries wished to be part of its prosperous journey. First was Greece in January 2000, followed by Denmark, Sweden, Finland, Norway and Iceland in March 2001. April of the following year saw the inclusion of Estonia, Czech Republic, Latvia, Hungary, Malta, Lithuania, Slovenia, Slovakia, and Poland, and landlocked Switzerland joined in October 2004. The desire for further cooperation rolled on and by the end of 2007 all member nations had abolished their land and sea borders, and this was followed up in March 2008 with the abolishment of airport controls.

The final country to become part of the Schengen Area and sign the Schengen Agreement was Liechtenstein in February 2008. This brought the total number of members to twenty-six.

There were few borders left now, and in March 2009 Switzerland had abolished their land and airport border controls which now left only one country to follow the others. This lead to the final important step of implementing the Schengen Agreement in December 2011 when the most recent member Liechtenstein finally declared the abolishment of its internal border controls – three years after signing.

Potential Schengen Area members

Simply being a member state of the European Union (EU) does not automatically make one a member of the Schengen Area, though technically in the long term this is a legally unavoidable development. The EU member countries described below are therefore in the process of joining, but for the moment have been denied inclusion due to their unresolved political issues.

The first example of a country in this situation is Cyprus which has been a member of the EU since 2004 but is not a member state of the Schengen Area. It is presently unable to sign the Schengen Agreement until it has resolved its issue revolving around its de facto divided island status and the political problems that this brings. Another issue concerns the handling of the British Sovereign Bases at Akrotiri and Dhekelia which are technically outside of the EU and which need specific solutions put in place before they can join the area.

Similarly, Bulgaria and Romania have been members of the EU since 2007 but are not members of the Schengen Area and have not yet signed the Schengen Agreement. Both of these countries submitted their request to become members of the area and their bids were initially approved by the European Parliament in June 2011, but their attempts were rejected later that year by the Council of Ministers. Heading this rejection were the governments of the Germany and Finland who expressed concerns over the lack of anti-corruption measures in place in the two countries and their lack of action against organised crime. They were also concerned about the mechanisms in place to prevent the entry of people from Turkey to Bulgaria and Romania who were then entering the Schengen Area illegally.

The next country on the list of potential Schengen Area members to sign the Schengen Agreement is Croatia. Despite having joined the European Union on 1 July 2013, Croatia is still not a member of the Schengen Area. The country does wish to join however and has clearly expressed its interest since March 2015. Since July 2015 the country has undergone a technical evaluation to assess its entry and is expected to meet the eligibility criteria in 2018.

Part of the problem has been due to the massive influx of migrants illegally entering the area initially through Greece, and following a path through Macedonia, Serbia then onto Croatia and into Slovenia, Austria, and Hungary. This has caused members to question the sustainability of the area and whether its enlargement is only going to inflame an already complex situation. In addition, member state Hungary, who had already been dealing with a large number of illegal entries across its border with Croatia stated that because of this it would vote against Croatia becoming a member of the Schengen Area.

Schengen Member States Territories that are not part of the Schengen Area

With the exception of the Canary Islands, the Azores, and Madeira, no other country that is located outside the continent of Europe is part of the Schengen Area or is a signatory to the Schengen Agreement. As such, this includes regions of France that are located outside of Europe – Guadeloupe, Mayotte, French Guyana, Martinique, Saint Martin, and Reunion which are all EU members but not members of the Schengen Area. This means that a Schengen Visa that has been issued by France is not valid in any of these territories. Therefore each of these territories operates their own visa policies to deal with controlling their borders in regards to non-members of the EEC (European Economic Area) and Swiss non-nationals.

In addition to this, there are several other French territories that are not members of the EU or the Schengen Area and which are all located outside of Europe. They are French Southern and Antarctic Lands, Caledonia, French Polynesia, and Wallis and Fortuna.

The Netherlands is also in possession of integral territories in the Caribbean that are in a similar situation to their French counterparts. These are Bonaire, Aruba, Saint Eustatius and Saba, Saint Martin and Curacao. None of these territories are part of either the European Union or the Schengen Area which means they also operate their own visa policy and regime.

Another unique case is the territory of Svalbard that has a special status under International Law but is not part of the Schengen area despite it being a Norwegian territory. The rules for entry state that any non-national who wishes to travel to Svalbard can only do so if they travel through the Schengen Area to get there first.

Two other interesting examples are the Danish territories of Greenland and the Faroe Islands. Neither of them is a member of the Schengen Area or the European Union. These means that to enter these areas travelers must get visas specifically from them – holders of visas purely from Denmark cannot get in. One additional clause, however, is that nationals from Nordic Passport Union member countries can simply use their ID to enter these two territories.